FDHS: Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences (2016)

Enactments of Identity

in the New Zealand Short Story

1 The New Zealander

New Zealand, as a nation, has been in existence for less than two centuries – whether one dates its assumption of sovereignty to the 1835 Declaration of Independence by the Confederation of United Tribes, the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi between Māori and the British Crown, or its attainment of Dominion status in 1907. The question of a separate cultural identity for this post-colonial, multi-cultural country has therefore always been a complex one.

Throughout the nineteenth century the term “New Zealander” meant a member of the native race of the country. The colonial population continued to refer to themselves as “English,” “British,” “French,” according to whichever nation they or their parents hailed from originally. In the twentieth century, however, “New Zealander” came to mean any member of the immigrant population, while the tangata whenua, or “people of the land,” came to be known as “Māori” (King 2007).

This system, similar in outline to the Latin American distinction between criollo (a native-born person of European ancestry), mestizo (a person of mixed race) and indio (a person of entirely native origins), nevertheless enshrines some rather different cultural assumptions. For a start, in New Zealand, as in all other Anglo-Saxon countries, there were no value-neutral terms for people of mixed race. The colour bar was absolute in both the American and British empires. You either were, or were not, white (Freyre 1966). If you were white in New Zealand, you might be referred to as a pākehā (a locally born person of European origin), or – if a more recent immigrant – by your home country. A series of mostly opprobrious terms such as “pommie” – which allegedly stands for “Proud of Mother England” – were accordingly created to distinguish such origins.

Hopefully this brief historical overview makes clear the intensely problematic nature of nationality – let alone identity – in a country such as New Zealand. There are, of course, precedents in countries such as Canada and Australia, with their own large European immigrant populations which have grown to outnumber – if not, as in Tasmania, displace entirely – the original native population.

What, then, does it mean to be called (or to call yourself) a New Zealander? The answer clearly depends on when the question was asked. As soon as the term had ceased to mean a native of the country, however, the problem of just what – if anything – distinguishes a New Zealand-born (or based) European from any other person of European origins began to loom large for locals. Gender equality also became an increasingly important part of the question as the twentieth century dawned. New Zealand was, after all, the first nation in the world to officially enact women’s suffrage.

•

2 Anthologies

The Arts are one of the places where we look for suggested answers to such questions of identity – to literature, in particular, whose basis in language has a tendency to encourage self-analysis as well as aesthetic evocation. It is pertinent, then, to remark that probably the most celebrated New Zealand-born literary figure to date, and by far our most distinguished writer of short stories, Katherine Mansfield, would have called herself English – albeit colonial English – rather than a “New Zealander.” In this she has more in common with the Anglo-Indian Rudyard Kipling or even such writers as Dominican-born Jean Rhys or Shanghai-born J. G. Ballard than with her local descendants.

Our national process of individuation (to adopt a term from psychoanalysis) has not, then, been a simple one. The main reason that Mansfield remains significant to us is not because she was born and brought up in New Zealand. She went to school in England, after all, and returned there to settle at the age of 19. It is the New Zealand setting and focus of her last, greatest stories, from “Prelude” onwards, which makes her so important. One could argue, however, that it is her outsider’s eye that made it possible for her to pick up on themes of social and racial prejudice to such telling effect. The local literary product in what was then still often referred to as “Maoriland” tended more to shameless Imperialism, Henry Lawson-style tales of larrikins and adventurers, and (interestingly enough) the odd venture into Wellsian or Jules Verne-like Science Fiction.

It is also true to say that it was leaving New Zealand – entering the literary world of London where she could encounter the cosmopolitan attitudes of Bloomsbury and the D. H. Lawrence circle – that enabled her to avoid such parochial imitations of Australian and American “frontier” literature. The same was true for later local female writers such as Jane Mander and Janet Frame, both of whom had to go elsewhere (New York, in Mander’s case; London, in Frame’s) to achieve recognition. Hopefully that situation has now changed for the better, but it is important to acknowledge this initial masculine and imperialist domination of the early twentieth-century New Zealand literary scene.

Given the limited time and attention paid to local writing (and culture in general) in pioneer and settler societies, it is also important to stress the somewhat disproportionate significance which continues to be attached to anthologies in so small a literary pool as New Zealand’s. To this day, the presence (or absence) of particular controversial figures from allegedly “representative” cross-sections of national work in one genre or another can be headline news in our country.

A writer can achieve great popular success and even bestseller status in New Zealand without ever attracting serious critical attention if they fail to figure in any of these canonical anthologies. A large part of the purpose of compiling such collections, in fact, is to call into question the aesthetic assumptions behind past exercises in canon-making. This is partly driven by economics (the logic of samplers rather than single-author collections in so small a market, which has only occasionally made inroads into the foreign publishing scene), and partially by our inheritance of European low culture / high culture assumptions along with so many other pieces of cultural baggage.

For the purposes of this essay, I have decided to look at four anthologies of local short fiction – Frank Sargeson’s Speaking for Ourselves (1945), Michael Morrissey’s The New Fiction (1985), Warwick Bennett & Patrick Hudson’s Rutherford's Dreams (1995), and Tina Shaw & Jack Ross’s Myth of the 21st Century (2006) – and to attempt to characterise their respective, overlapping visions of New Zealand identity by conducting a close reading of a representative story from each of them.

This list may seem, at first sight, a somewhat eccentric one. Where, for instance, is Dan Davin’s 1953 World’s Classics collection of New Zealand Short Stories (co-edited by Eric McCormick and Frank Sargeson)? Where is C. K. Stead’s 1966 follow-up volume? Where, above all, is Marion McLeod and Bill Manhire’s immensely successful Some Other Country: New Zealand’s Best Short Stories, first published in 1984, and subsequently revised and reprinted on numerous occasions?

It would be unfair to claim that there is little to choose between these collections. Each one of them makes interesting claims about the growth and progress of short fiction in this country, but I would nevertheless see each of them as committed to a Sargesonian view of the importance of the local realist tradition. As far as the questions of national identity addressed by this essay are concerned, there’s little I could say about them which cannot be said in connection with Sargeson’s own, defiantly titled Speaking for Ourselves anthology.

My rationale for discussing only a single story from each is partly expediency: characterising the contents of any considerable collection of stories tends to turn into a set of truncated truisms about each one. My larger intention will, I hope, become more apparent as the essay proceeds. It is to trace the evolution of a certain type of “everyman” figure in local writing as it accomplishes its transformation from realism to a more nuanced set of fictional alternatives.

•

3 Speaking for Ourselves

In 1945, New Zealand’s then foremost literary publisher, Caxton Press, issued an anthology of short stories entitled Speaking for Ourselves. It was edited by Frank Sargeson, then a little-known writer eking out a precarious living as a market gardener on the North Shore of Auckland, the country’s largest city, but already the author of two significant books of short fiction: Conversation with My Uncle (1936) and A Man and His Wife (1940). The London publication, in 1946, of his next collection That Summer and Other Stories would establish him as one of the most influential voices in New Zealand writing: the first (among other distinctions) to introduce a still-recognizable form of local vernacular into our fictional tradition.

Speaking for Ourselves seems more important in retrospect, then, than it can have done at the time. For a start, it was only 123 pages long, with fifteen stories by such later luminaries as Roderick Finlayson, A.P. Gaskell, David Ballantyne, John Reece Cole, and Maurice Duggan (a group subsequently known as the “Sons of Sargeson,” though this greatly exaggerates the similarities between them). It also contained one of Sargeson’s own most famous stories, “The Hole That Jack Dug,” along with pieces by writers as diverse as poet Helen Shaw and Spanish civil war veteran Greville Texidor.

Speaking for Ourselves. It is an interesting title, which only really makes sense in terms of the brief potted history outlined above. Who, to start with, were “ourselves” – and how were we to “speak”? The centenary of the signing of the Treaty of Waitangi, the founding document for British sovereignty over New Zealand, fell in 1940. There were therefore a number of nation-building exercises going on throughout the decade designed specifically to address such questions. Local Top Bard Allen Curnow was commissioned to write a poem, “Landfall in Unknown Seas,” which was duly set to music by our most prominent composer, Douglas Lilburn. A series of “Centennial Survey” volumes were published by the Government Department of Internal Affairs.

In the same year as Speaking for Ourselves, Allen Curnow’s rather more controversial Book of New Zealand Verse was also published by the Caxton Press. Like Sargeson, Curnow was intent on establishing a new canon for New Zealand poetry, purging a number of celebrated writers (mostly female) whom he considered insufficiently intellectual to establish a worth-while native tradition. In its various forms, culminating in the Penguin Book of New Zealand Verse of 1960, Curnow’s anthology set up a conversation which continues to this day about the precise nature of New Zealand nationhood. It is untrue to say that there were no women or Māori in Curnow’s vision (though the latter had to wait till the 1960 edition to be represented even in translation). It was certainly intended to be rigorously hard-edged and Modernist in its bias, however.

Sargeson’s anthology, perhaps because it lacked the lengthy theoretical introduction Curnow had provided, made rather less of a stir. It did, however, strongly influence the composition of two influential successors, the British World’s Classics volumes of New Zealand Short Stories edited (respectively) by Kiwi ex-pat Dan Davin in 1953 and C. K. Stead in 1966. Between them, these three anthologies of short fiction established a local realist tradition, often referred to – in retrospect, at least – as “Settler Realism.” It was not until the 1970s that indigenous voices began to be heard in New Zealand writing, and then (for quite some time) only in the person of Māori writer Witi Ihimaera.

How, then, did Sargeson envisage our “speaking for ourselves”? To a large extent what he had in mind was inspired by American precedents: Mark Twain’s nineteenth-century vernacular masterpiece Huckleberry Finn, above all, as well as such successors as Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio (1919). He found in such books a close attention to details of local speech, together with a well-developed social conscience. Given the dominance of British culture in our writing up to that point, perhaps Sargeson’s most important innovation consisted simply of acknowledging the existence of an alternate, New World tradition – most accessibly represented in the literature of the United States.

•

3.1 The Hole that Jack Dug

Perhaps the best way of describing Sargeson’s decisive influence on New Zealand short fiction is, however, to analyze one of his most famous short stories, “The Hole that Jack Dug”, which he himself selected to showcase his own work in Speaking for Ourselves.

The story begins with disarming simplicity:

Jack had got a pretty considerable hole dug in the backyard before I knew anything about it. (Sargeson 1946: p. 179)

This tells us quite a few things to start with: first, that the narrator is well enough acquainted with Jack to expect to know that he is digging a hole in his backyard; secondly, that the story will indeed concern a literal hole, dug by the character Jack; thirdly, that it will most likely take the form of an anecdote about one man shared by another to an undisclosed audience.

I went round one scorching hot Saturday afternoon, and Jack was in the hole with nothing on except his boots and his little tight pair of shorts. …

Hullo, Jack, I said, doing a spot of work? (p. 179)

New Zealanders (in fiction, at least) tend to speak almost as laconically as some of the deadpan characters in the Icelandic Sagas. Certainly the action in a Sargeson story mostly goes on behind the lines of the dialogue. Little will be said by either Jack or his friend in the story to reveal the true meaning of this “spot of work.”

Who is Jack, anyway? Well, he’s “a big specimen of a bloke … very powerfully developed, and seeing he’s worked in the quarry for years in just that rigout he’s browned a darker colour than you’d ever believe possible on a white man.” There’s nothing at all aristocratic about him, in other words. He works hard at hard manual labour, and he’s browner than – it is implied – any truly white, European man should be:

Also, his eyes are sky-blue, and it almost scares you to see them staring out of all that sunburn. I don’t say they don’t fit in though. They always have a bit of a crazy look about them, and even though Jack is my closest cobber, I will say he’ll do some crazy things. (p. 179)

There’s a strong hint that Jack is not very reliable: “crazy”, even – the word is repeated twice. I think that we are already beginning to have doubts about the nature of the hole that Jack is digging. Does it have a use, or is it just another of the “crazy things” he does? (I should explain further that the Antipodean term “cobber” translates as a mate, a very close male friend).

The narrator “was just going to ask Jack if he wanted a hand, when his missus opened the back door and asked if I’d go in and have a cup of tea.” So appears our third actor, Mrs. Parker, Jack’s wife (or “missus”), and thus (after this initial scene setting) our drama begins.

She didn’t ask Jack, but he said he could do with one, so we both went inside, and his missus had several of her friends there. She always has stacks of friends, and most times you’ll find them about. But I’m Jack’s friend, about the only one he has that goes to the house. (pp. 179-80)

I think we can see at once that there’s some tension between this couple: the wife inside the house, with her “stacks of friends,” who does not even ask her husband if he would like a cup of tea, and Jack, outside, burned brown, working hard in the garden. It is a little parable of colonialism, if you like: the men working hard to create a simulacrum of Englishness in a far-off, alien country - if that is what they are doing.

At this point we get a bit of necessary backstory. The narrator has already mentioned that the weather that day was so lovely “you just couldn’t believe there was any war on,” and now he tells us that he first met Jack “in camp during the last war.” They met during World War I, in other words, and by now World War II is raging. This informs us that they are both middle-aged men, in their forties at least, and that they have known each other for a considerable amount of that time.

In those days he hadn’t started to trot the Sheila he eventually married, though later on when he did I heard all about it. … He was always telling me about how she was far too good for him, a girl with her brains and refinement. Before she came out from England she’d been a governess (p. 180).

“Trot the sheila” is New Zealand slang for courting, or walking out with a girl – the fact that the narrator puts it that way does seem to imply a considerable amount of doubt on his part that this English girl really is “far too good” for his friend – though she undoubtedly believes it to be so.

As the story continues, the hole – the inexplicable, illogical nature of the hole – begins to loom larger and larger:

That hole!

It was right up against the wash-house wall, and we went out and looked at it, and Jack said it would take a lot of work but never mind. … we could widen it another four feet so the pair of us could work there together. (p. 182)

The fact that it is against the wall implies strongly that Jack doesn’t care if it undermines the foundations – and the fact that he can widen it so casually by four feet (over a metre) tells us that its precise dimensions aren’t of any great significance either.

The “I” of the story knows Jack too well to ask him directly about the hole, but “thought if I just kept my mouth shut I’d find out in plenty of time what he was digging it for.” As it turns out, though, he is not the one who asks: Jack’s wife is:

Whatever are you two boys doing? She wanted to know.

We’ve been working, Mrs. Parker, I said.

Yes, she said, but what are you digging that hole for?

You see, dear, Jack said, some people say they don’t like work, but what would we ever have if we didn’t work? And now the war’s on we’ve all got to do our share. (p. 183)

The answer he gives is, as might be expected, no answer at all. The narrator continues to wonder about it, though: “perhaps it was a septic tank he was putting in. Or was it an asparagus bed? Or was he going to set a grape vine? It was evidently going to be a proper job anyway, whatever it was.”

The digging goes on and on. The hole gets bigger and bigger, even requiring blasting when they strike rock. Finally, after “several weeks,” during which “Jack hadn’t done a tap of work in the garden” Mrs. Parker came out with two cups of tea, and “said he must be losing his eyesight if he couldn’t see there was plenty just crying out to be done.”

Yes, dear, Jack said in that good-natured sort of loving tone he always uses to her. Things being what they are between them, I can understand how it must make her want to knock him over the head. Yes, dear, he said, but just now there are other things for Tom and me to do. (p. 185)

Note, though, that his wife has come out of the house with the tea this time – a shift from not even bothering to ask him if he wanted one at the beginning of the story. There are two cups, too – not simply the one she then offered their “guest”. Somehow the hole has served its purpose – its sheer irrationality and threatening, void-like emptiness has given Jack the upper hand over his wife’s social pretensions.

And so the story ends. “Next time I went round he was filling it in again, and he’d already got a fair bit done. All he said was that if he didn’t go ahead and get his winter garden in he’d be having the family short of vegetables.”

Nothing is, in the end, resolved. The tensions remain strong between husband and wife – Jack and his cobber go on working together in the garden. And yet his strange acte gratuit has had its effect. His individuality remains unfettered. He is, in his way, as free a spirit as Camus’s outsider Meursault (in his 1942 novel L'Étranger) – though it is strongly implied that he risks ending almost as badly as Camus’s character.

As for me, I’m ready to stick up for Jack any time. Though I don’t say his missus is making a mistake when she says that some day he’ll end up in the lunatic asylum. (p. 186)

•

4 The New Fiction

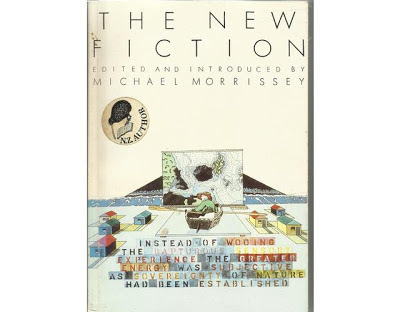

In 1985, exactly 40 years after Frank Sargeson’s pioneering work, local writer Michael Morrissey published an anthology called The New Fiction. The “New Fiction” he had in mind was the game-playing post-modern and metafictional writing of the 1960s and 70s.

Where, behind Sargeson, one could sense the looming presences of American writers such as Mark Twain, Ernest Hemingway, and William Faulkner – both in their insistence on treating the male vernacular voice as primary, and their privileging of the primal and direct over the courtly and artificial – so Morrissey, in the long critical introduction to his anthology, makes no secret of his adherence to a new set of American writers: fabulists such as John Barth, Donald Barthelme, and Thomas Pynchon (not to mention their foreign-language progenitors Jorge Luis Borges, Franz Kafka and Italo Calvino).

Morrissey’s anthology set out to make an explicit challenge to the prevailing realist paradigm of the New Zealand short story. In line with developments elsewhere in the Arts in the 1980s in New Zealand, it strove to replace the local brand of self-conscious expressive nationalism with a new kind of rootless cosmopolitanism.

Morrissey’s venture cannot by any means be described a failure. His anthology drew attention to a number of writers – Keri Hulme, Russell Haley, and Stephanie Johnson among them – who would go on to establish themselves as major voices in New Zealand fiction in the coming decades. Many of the other authors he included have, however, achieved more recognition as poets than fiction-writers. But as the harbinger of a new cultural movement, The New Fiction must be acknowledged to have missed fire – perhaps partly because his preface made such grandiloquent claims for these “new trends” in our literature.

It is probably fair to say that this was as much due to the laziness of an entrenched Academic and critical establishment as to any vital sense of the continuing relevance of unvarnished realism to the national conversation. Metafiction may have failed to replace Settler Realism outright, but the former was clearly here to stay. It may seem like a coterie interest, but in a literary pool as small as ours, distinctions between what is “mainstream” and what “peripheral” can be difficult to substantiate.

•

4.1 Jack Kerouac Sat Down beside the Wanganui River and Wept

Again, perhaps the best way to characterize Morrissey’s anthology is to analyse one of the stories in it, and his own “Jack Kerouac Sat Down beside the Wanganui River and Wept” seems ideally suited for the role.

The point has possibly been made before, but the repetition of the name “Jack” in his title does seem a bit more than a coincidence. It might be an exaggeration to see his story as a direct riposte to Sargeson’s own spare, elegant tale, but there are nevertheless certain affinities between the two. A “Jack” is, after all, a slang term for a man (a “Jack-tar” for a sailor, “every man jack” for every person). Certainly, if this is so, the Jack of Morrissey’s tale has morphed considerably from the sunburnt, misogynist anarchist of Sargeson’s.

In form, Morrissey’s story is explicitly modelled on such works as E. L. Doctorow’s 1975 novel Ragtime, where “real” and “fictional” characters cohabit in the same syncopated narrative, as the former makes clear in his introduction to the anthology. His title also makes an allusion to Canadian writer Elizabeth Smart’s poetic novella By Grand Central Station I Sat Down and Wept (1945), a phrase derived, in its turn, from the Biblical Psalm 137, where Hebrew slaves lament their exile from Israel:

By the rivers of Babylon, there we sat down, yea, we wept, when we remembered Zion.

The spirit of exile which is so strong in the story is, then, initially Kerouac’s – in flight from his homeland and the suffocating household of his domineering mother “Memère” – but it also applies to most of the other characters in the story, lost as they are in a postcolonial wilderness of contradictory signs.

Let me unpack that last phrase a little. In Morrissey’s story, the American Beat writer Jack Kerouac (1922-1969) is hitchhiking his way through the North Island of New Zealand – which he in fact never visited – in search of the grave of one of our greatest poets, the religious visionary and social revolutionary James K. Baxter (1926-1972). As you can see from the dates, this is quite clearly impossible, as the latter died three years after the former. The story must therefore be intended to serve as some kind of vision quest, rather than any more “realistic” act of historical reconstruction.

Having established the impossibility of the scenario he is describing, Morrissey tries to persuade us of its intense desirability – its rightness, if you prefer:

Late on Christmas Day Jack Kerouac was hitching through Putaruru with a Maori driving a 1967 Falcon Ute. The town was so quiet – even the Takeaways were closed – that Jack said, ‘Are they making a film here?’

‘Not in Putaruru,’ said the Maori laughing. ‘They made an ad here once.’

‘They did!’

‘Yeah,’ nodded the Maori, ‘about the end of the world,’ his body shaking so violently Jack Kerouac could hear the forty-five cents in his pocket begin to jingle. (Morrissey 1985: p. 125)

Just as the “Jack” in Sargeson’s story has been scorched by the sun until he looks too dark for a respectable white man, so Jack Kerouac in Morrissey’s piece instinctively sides with the underdog: with the Māori in his Ute with only 45 cents in his pockets, and with the various other drifters and outsiders he encounters in the course of the narrative.

In this he establishes a clear affinity with Baxter himself, who renounced his own worldly possessions to go and live in a commune at Jerusalem on the Wanganui River, in one of the most distant and poverty-stricken regions of New Zealand: Baxter, who dressed in rags and walked barefoot, and wrote of the sufferings of the tangata whenua, the people of the land, as if they were his own.

There’s nothing pompous or stuffy about Morrissey’s story, however – like any good student of Kerouac’s classic novel On the Road (1957), his characters are out mainly for a good time. There is a lot of sex in the story, a lot of hard drinking and random driving. But that is what makes it such a good simulacrum of a classic “Beat” story.

Perhaps the most marked change between the world of Sargeson’s story and the world of Morrissey is the increased attention to and sympathy for women. Admittedly, women’s attitudes are shown to have changed greatly since the 1940s:

The girl shot him a Tantric look.

‘Why don’t we stop the car,’ Jack said.

The girl stopped the car on the edge of a cliff and kissed him.

She had a stronger tongue than Jack’s so when they parted he felt as though the top of his head had been hit with a tyre mallet from the inside.

Then they got out of the car, lay in the warm grass over the river and made love.

Jack was underneath. (p. 129)

Fundamentally, though, Morrissey’s prose hymn to life is a love story: love for Jim Baxter, at whose picturesque grave by the side of the river the story concludes, but also love for Kerouac himself, for everything that man represented to the repressed kids of the 1950s and 60s. We all owe an immense debt to him and his friends Allen Ginsberg and Neal Cassady (and even William Burroughs) for blowing sky-high the conventions of a violent, emotionally constipated society – like the one sketched in so lightly as the backdrop to Sargeson’s own “Jack” story.

In critical terms, though, the story itself is revolutionary. Its symbolic intentions are nothing new for New Zealand fiction: as we have seen, Sargeson himself has strong designs on the reader, and a revulsion from the puritanical attitudes of colonial New Zealand. Morrissey, however, eschews even the appearance of realism in his own story. It is not that the settings are unreal: rather, that by putting this larger-than-life character into action within them, we begin to see the essential arbitrariness of such artistic constraints.

Morrissey may not be Kafka, exactly – his tone is too lighthearted for that – but his work has a far stronger affinity with the Metafiction and Magic Realism so clearly in evidence in other parts of the English-speaking world than had hitherto been regarded as possible for local writers. With the exception of the work of his older contemporary Janet Frame – mostly published overseas – this was the first time a strong claim had been made here for the possibility of a fiction which need not be purely realist.

•

5 Rutherford’s Dreams

In 1995, fifty years after Speaking for Ourselves, Wellington Publisher IPL Books issued an anthology entitled Rutherford's Dreams: A New Zealand Science Fiction Collection.

There are some interesting remarks in the Introduction by one of the editors, Patrick Hudson. He begins by pointing out how few people read books of poems by comparison with those who read science fiction, then claims that “if you look at the magazines that publish original writing in New Zealand, and if you review the books published in New Zealand over the last twelve months, you will see that while poetry is thriving, science fiction does not appear to exist.”

This is a conundrum. How could poetry, a minority interest at best, have such a high profile while science fiction, a supposedly “popular genre” languishes in the doldrums? Certainly the “popular genres” are regarded as commercially viable by the Arts Council and “in less need of a subsidy”. But if this is so, where are they? (Hudson 1995: p. 7)

The reason for this, he goes on to explain, is that the only practical way of making a living as a writer in a market as small as ours is through “literary grants and prizes”:

… a brisk seller in New Zealand, say 1500-2000 copies, will eventually yield its author $3,000-$4,000 before tax … While modest by international standards, an established writer’s grant for the Arts Council can easily exceed the royalties from a dozen novels (p. 7)

Since the people who award such grants tend to be academics and critics, it is not surprising that the writing they favour tends to be “academic, literary and resolutely mainstream: genre authors need not apply.”

Given that money is limited, who should get the support of the state and why? Is science fiction, and genre fiction in general, inherently inferior in intent and execution to “literary” fiction? … In the 20th century, science fiction has a special place in highlighting issues that arise from the western rationalist tradition that began with the scientific method. It is perhaps partly because of challenges to this ideology that science fiction has a bad reputation, and yet no other genre is better equipped to examine the claims and contradictions of scientific thinking than science fiction. (pp. 8-9)

Hudson’s remarks are difficult to refute. Nor are the stories included in his anthology without interest, although the best of them do tend to come from the most prominent authors: Phillip Mann, Vivienne Plumb and Elizabeth Smither among them. Many of the others are (as Hudson himself acknowledged) “a little raw and undeveloped.”

The situation is not dissimilar in another anthology, Tales from the Out of Time Café, published a year later by Phillip Mann and his friends from the Phoenix Science Fiction Society of Wellington. Once again, the best of the stories are by Mann himself, and the appeal of the volume as a whole lies largely in its good-humoured satire at the expense of science-fiction clichés past and present.

•

5.1 Lux in Tenebris

There’s a great variety of work included in these two “NZSF” anthologies. The linked stories in the Tales from the Out of Time Café anthology are difficult to discuss out of context, so I have chosen instead to talk about one of the two Phillip Mann stories included in Rutherford’s Dreams.

Mann’s writing – unlike, say, Michael Morrissey’s – does not tend towards metafictional self-consciousness, though he does show a close knowledge and deep affection for the mainstream science fiction tradition. “Lux in Tenebris” is interesting partially as a recasting of H. P. Lovecraft’s classic horror story “The Color Out of Space” to medieval Europe, but its basic metaphor of light emanating from a deep hole might be claimed, once again, as a nod to Sargeson’s classic “Hole that Jack Dug.”

Whether you accept that reading or not, the story certainly represents a departure from the local settings of both Sargeson’s and Morrissey’s own stories. It is placed at a considerable distance from here, both in time and space, and the issues it looks at are only tangentially concerned with New Zealand, let alone New Zealand identity. It is, in fact, more concerned with an examination of “the claims and contradictions of scientific thinking,” as Patrick Hudson suggests in his Introduction (quoted above).

“Lux in Tenebris,” one might add, is set at an almost equal distance from Phillip Mann’s native Yorkshire and his adopted homeland of New Zealand: it takes place in medieval France. It tells the story of a stonemason called Gerard who is unfortunate enough to have a close encounter of the third kind with some aliens – “wedge shaped figures in white … with stumpy arms like exposed intestines and legs like inflated bladders.”

But the heads … They were shiny black balls reflecting the forest canopy where it was caught in the light. Gerard stared at them and saw his own face reflected … to himself, Gerard looked like a ferret. (Mann 1995: p. 95)

In exchange for one of his tools, his mallet, they leave him a kind of torch that gives out blue light. In terror for his soul, Gerard drops the torch in the village well, and the illumination it provides turns the spot into a Lourdes-like place of pilgrimage.

Six months later, the light finally gives out, and the well starts to stink. The water from it “tasted sour and burned the lips.” As the contamination from it starts to spread, the villagers are forced to flee. Gerard, too, takes his family and starts a new life in a “town close to the sea,” where he is able to find work “repairing sheepcotes with stones taken from an old Roman theatre.”

Many years later, business takes Gerard close to his old village, and he decides to take his eldest son to see the place where he was born. While there, he takes the opportunity to check the place where he had met the strange beings, which, at the time – like any classic UFO landing site – displayed signs that “something huge had rested here."

It had pressed the bushes so flat that they were indented into the forest floor. Three small areas had been completely cleared, down to the soil … To his countryman’s eyes it was obvious that something had been planted … or buried. (p. 101)

Now, a couple of decades on, these spots have given rise to some “coal black” trees with bark of the “same soft living texture as the velvet which covers the antlers of a young stag.” When Gerard reaches out to touch them, “he felt a mild sting in his finger ends.” (pp. 110-11)

In the hills, looking back, Gerard and his son can see “a black stain which was spreading over the forest like a mantle of darkness, like the shadow of Satan himself, and which was probing into the valleys and had reached to the very edge of the valley beneath them. Faintly they caught the aroma of lemons.” (p. 112)

On the one hand, the story is clearly about the blindness of faith. Bishop de Lautremont, a believer in the miraculous nature of the light from the well, partially because “the colour of the light from the well was close to that of the cape worn by the Virgin Mary in the stained glass window of the monastery chapel” (pp. 98-99), dies in despair, having convinced himself that it is his own sins which have transformed it into a stinking pit of darkness.

The abbot of Langevin, by contrast, “saw an end to revenue and gave vent to a righteous anger” when the light went out. The change, as he saw it, must be due to some sinful act on the part of the villagers themselves.

“This is a punishment. How can it be other than a punishment? Someone has fostered evil. And this place of light and healing and miracle is become an abomination … Pick out the evil doer. Root him out I say … for the fires of Hell are eternal and the pain is everlasting” (p. 106)

On the other hand, the story reads like a reprise of some of the themes of Mann’s almost exactly contemporaneous A Land Fit for Heroes tetralogy (1993-1996), in which he imagines an alternate present where the Roman empire never fell but instead continued to thrive. That series, too, ends with an act of environmental catastrophe which leaves the fertile and still forested land of Britain overhung by a great toxic cloud of blackness.

The exotic settings of both his tetralogy, and “Lux in Tenebris” itself, may also be intended by Mann to point out some of the limitations of sticking solely to homegrown, autobiographical writing: the Settler Fiction tradition which has dominated our literature for so long. Morrissey may have imported a “Jack” from outside, but he placed him in a firmly local context. Mann’s “Gerard” lacks even residual “New Zealandness.” He simply faces some of the same dilemmas we do: how to act in dangerous situations we barely understand, and how to resist the premature assertions of knowledge imposed by official culture.

Certainly, none of the events in the story are Gerard’s fault, exactly; he’s more of a hapless victim than an actor. His decision to throw the torch in the well was probably unwise, but that had nothing to do with the three trees left in the clearing, so whatever the true intentions of these visitors, their work was already well begun.

Gerard’s plight seems more symbolic of the fate of indigenous people everywhere, in fact. He takes the poisoned gift against his will, and his attempts to flee the consequences are only partially successful. While it is certainly not a hopeful tale, “Lux in Tenebris” is perhaps best seen as a warning: ignorance is not always a defence against evil, and those who bring contamination often do so with the very best of motives. It is also, of course, strongly suggestive of the environmental dangers that overshadow us all as we continue to sacrifice prudent self-interest to the ever-increasing demands of our technology.

There is a marked absence of female agency in Mann’s story. The “wedge shaped figures in white” whom Gerard initially encounters are unisex enough, but the pollution they leave behind them has a definite flavour of man-made scientific madness. The Bishop, then, is cruelly deceived when he sees a colour in the well reminiscent “of the cape worn by the Virgin Mary in the stained glass window of the monastery chapel.”

Like the hole at the centre of Sargeson’s story, the meaning of the well is, finally, ambiguous. It is true that Gerard has, in a sense, created it – as a place of pilgrimage, at any rate – by attempting to hide the torch in it. His act brings disaster to the village and all its inhabitants, but it is hard to see that as his fault, exactly. He is portrayed throughout as more of a victim than a perpetrator of evil.

The original Jack’s hole can be seen, in retrospect, as a device for maintaining the balance of power with his too-dominant “Missus.” The threat of insanity and pointlessness it poses is too much, finally, and she is forced to concede him some measure of autonomy. Michael Morrissey’s Jack is similarly interested in avoiding close ties. He rejects domesticity and order, and pays homage (at the end of the story) to a poet who left his wife and family to pursue the way of renunciation and pilgrimage.

The hole at the centre of Mann’s story might be seen as satirical of both attitudes. Gerard is too concerned with bare survival to concern himself with the local power structures. The pilgrimage at the centre of this narrative is entirely fruitless and based on misapprehension. Mann’s work concerns itself with the global themes of modern “climate fiction,” rather than the narrower concerns of the small nation he lives in. Partially this is simply as a consequence of the genre he has chosen to write in, Science Fiction, but it must be seen as a heartening development to reflect that this, too, can now be regarded as a practical choice for a New Zealand short story writer.

•

6 Myth of the 21st Century

In 2006, sixty years after Frank Sargeson, twenty years after Michael Morrisssey and ten years after Warwick Bennett and Patrick Hudson, novelist Tina Shaw and I published another anthology of new fiction. We called it Myth of the 21st Century. In it, we attempted to combine the best of these traditions alternative to mainstream NZ Settler Realism: Fantasy, Metafiction, Fable and , and SF (whether defined as “Science” or “Speculative” Fiction). We also included a number of Māori and Pasifika writers, whose input seemed to us essential for any collection aspiring to be representative of contemporary trends in the New Zealand short story.

In the introduction, we tried to sum up our own understanding of myth, the central metaphor of the collection:

In a recent NZ Herald column, Colin James suggested that “a society needs myths to hold it together. A nation is woven out of fictions, agreed from experience and from artists’ and writers’ imaginings drawn from that experience.” That is indeed the positive side of the picture — myths as shaping archetypes, agreed-upon fictions, essentially harmless ways of arranging an experience we all share but cannot easily express. If myths are lies, then they are, in C.S. Lewis’s words, “lies breathed through silver.”

This is a persuasive view, but it hardly does justice to the other side of the coin: myths as monstrously damaging illusions, concerted denials of the actual nature of things — the myths of male superiority, of racial purity, of divinely appointed missions. Nazi ideologue Alfred Rosenberg wrapped it all up in one convenient package in his notorious Myth of the Twentieth Century (1930), a comprehensive overview of the imaginary “Jewish world conspiracy” which somehow manages to tie in Bolshevism, cocktails, jazz and anything else he and his National Socialist friends happened to disapprove of. (Shaw & Ross 2006: p. 6)

We concluded by saying:

Like it or not, we’re stuck with them, so it makes sense to inquire into their nature as often and as deeply as possible. … And if we writers, the licensed myth-spinners of society, don’t start that process, who will? (p. 7)

•

6.1 The Isle of the Cross

To conclude this brief overview of how competing concepts of New Zealand identity have informed successive collections of our short fiction, I’ve decided to discuss “The Isle of the Cross”, my own contribution to our joint anthology. This is partially because it is – for obvious reasons – the story I can say most about firsthand, but also because it lines up quite neatly with the other stories so far examined. Like Phillip Mann’s, my story is meant as an examination of the theme of eco-catastrophe. Unlike his, however, mine does not attribute it to outside influences, but to our own willful blindness:

We were mismanaged. We didn’t listen, even when there might have been a chance to do something — about the haze of greenhouse gases, the break-up of the great ice-shelves of the south. It’s true no mere budgetary readjustments could have stopped it, but maybe, just maybe, if we could have agreed to suspend the spree, cut back a little.

Agreed! When did we ever agree on anything? We squabbled, fought, and screamed at one another as the waters rose. As all hope disappeared. (Ross 2006: p. 85)

The unnamed narrator writes his story in the margins of a lost novel by Herman Melville: or, rather, alternates his own experiences with an account of the few clues remaining to us as to the nature of that work.

“In a 24 November letter to the Harpers, Melville used phrasing that implied that the firm had not simply rejected The Isle of the Cross but that he somehow had been prevented from publishing it, as if it were somehow not simply a matter of their not liking it,” conjectures Hershel Parker in his definitive biography. “The most obvious guess is that the Harpers feared that their firm would be criminally liable if anyone recognised any surviving originals of the characters.” (p. 85)

In this respect, my story might be said to bear a stronger resemblance to Morrissey’s than Mann’s. Just as Morrissey felt a need to transplant the freewheeling ways of Jack Kerouac to express the “end of the world” of backblocks New Zealand, so the strange sentimentality of what Melville referred to as “the Agatha story” – in a letter to Hawthorne, whom he initially exhorted to write it – seemed to me to add the necessary note of pathos to my rather hopeless protagonist’s plight.

Given my narrator is unnamed, and that that my own first name is “Jack,” this might equally well be seen as an allusion to the “Jack” of Sargeson’s “The Hole that Jack Dug.” They do, after all, share a location: the city of Auckland, and a preoccupation with gardening as a means of subsistence and survival! The story itself describes the protagonist’s attempt to rescue a young Asian woman whom he finds living in an abandoned, partially-flooded building near his own home: “Chinese, perhaps? Korean? Maybe with a touch of Kiwi mixed in.” (p. 88) Her name is Dai-Yu.

The attempt is unsuccessful. As soon as she senses his desire to control and own her, she leaves:

There was no note, no attempt to explain. What, indeed, was there to explain?

Had I hoped she would stay, tend to the house while I went out scavenging for food? Create a little simulacrum of a family in this dank, rotten house? My selkie wife? Seal-woman from the sea?

S O R R Y was traced in salt on the kitchen table.

I like to think, had she had the time, she might have added: ‘Thanks.’ (p. 93)

Melville’s lost novel, too (it seems), was a story of hope deferred. The main character, Agatha, had saved a man named Robinson from a shipwreck. After his departure from her remote house he promised to write to her:

Owing to the remoteness of the lighthouse from any settled place no regular mail reaches it … at the junction … there stands a post surmounted with a little rude wood box with a lid to it & a leather hinge. Into this box the Post boy drops all letters ... And, of course, daily young Agatha goes — for seventeen years she goes thither daily. As her hopes gradually decay in her, so does the post itself & the little box decay. The post rots in the ground at last. Owing to its being little used — hardly used at all — grass grows rankly about it. At last a little bird nests in it. At last the post falls. (p. 92)

At least, that’s how Melville described the plot in his letter to Hawthorne. The choice of the name “Dai-Yu” for the young girl in my own story was meant as a nod to Lin Dai-Yu, one of the main characters in Cao Xue-qin’s classic Chinese novel The Red Chamber Dream. I wanted to lend my own character something of the same tragic, waif-like innocence. The story, then, is not hopeful in the traditional sense: like Morrissey’s and Mann’s, it ends on a note of mourning (and warning). But if there is any hope left in the narrative, I meant for it to remain with this girl:

Godspeed, Dai-yu. I hope that you, at least, escape our wreck.

The story proper concludes, however, somewhat more parasitically: by quoting the conclusion of Melville’s own greatest novel, Moby-Dick:

Now small fowls flew screaming over the yet yawning gulf; a sullen white surf beat against its steep sides; then all collapsed, and the great shroud of the sea rolled on as it rolled five thousand years ago. (p. 94)

This “gulf” might be seen symbolically as an extension of Jack’s hole in Sargeson’s story, growing and growing until it threatens to swallow up all the neat little houses around it. The extent of the catastrophe ties in, too, with the black blight of industrial poison spreading out from the well in Mann’s story (just as it does, increasingly, in reality). Mainly, though, I meant my character to seem like the last colonialist, the last hopeless idealist trying to make his garden bloom in an alien land.

It is not that this is in itself a pointless or uncreative act. It is simply that it has – in the past two hundred years of European occupancy and invasion of New Zealand, like so many other stolen tracts of territory – brought with it a series of racist, sexist and finally exclusionist attitudes with which we are only now beginning to come to terms.

My character fails, of course. But perhaps his failure might be seen as more promising than the partial success of the main character in “The Hole that Jack Dug.” That Jack was able to impose his will, but at a crippling price to his sanity and sense of self-worth. My “Jack” learns that the attempt to dominate and control others – with whatever good intentions – leads only to recrimination and misunderstanding in the end.

•

7 The Future

In conclusion, then, while it is clear that the idea of “Speaking for Ourselves” can be as damaging an illusion as the notion that European culture can be transported bodily across the globe and transplanted even in so distant an outpost of Empire as New Zealand, it is true to say that each admittedly partial attempt to define what it is to be a New Zealander has taught us something – if only how little, in the long run, we know about anything.

The myth of a stable New Zealand national identity is clearly as damaging an illusion as any. It is genuinely astonishing, I think, to contemporary readers than any such definition could ever have been attempted without careful and whole-hearted representation of the original people of the land, and their own right to “speak for themselves.”

It would, of course, be possible to write a more optimistic history of New Zealand short fiction if one were to concentrate solely on the many fascinating female writers who have illuminated the form: Katherine Mansfield, Janet Frame, Fiona Kidman, Patricia Grace, Keri Hulme, and Tracey Slaughter are all important figures in that resplendent genealogy. Each one of them has, however, had to define herself against a dominant literary agenda which may have morphed from settler to bourgeois realism, but which still sees certain types of experience – and the portrayal of experience – as inevitable.

I have therefore had to ignore, reluctantly – for the moment, at least – this fascinating counter-history in favour of a rather narrower account of the growth of a global consciousness (both in theme and the possibility of alternative narrative modes) in the short story here.

The New Zealand of the 21st century is not simply bicultural, it is increasingly multi-cultural. Chinese and Indian New Zealanders face their own crises of identity as they attempt to write a solution to the problem of – in Allen Curnow’s famous words – “standing upright here” (Curnow, 1997, p. 220). Ten years on from Tina’s and my anthology I begin to see room for a new one: one which could blend the gender-bending outsider voices of Māori writer Alice Tawhai with the violent antitheses of contemporary Pākehā writers such as Breton Dukes or Tracey Slaughter.

Perhaps, then, each of us might aspire, finally, to “speaking for ourselves” – when it has become clear to all just how individual and contingent a claim that is always going to be.

•

References:

Curnow, Allen. (1997). The Skeleton of the Great Moa in the Canterbury Museum, Christchurch. In Early Days Yet: New and Collected Poems 1941-1997, 220. Auckland: Auckland University Press.

Freyre, Gilberto. (1966). The Masters and the Slaves: A Study in the Development of Brazilian Civilization, trans. Samuel Putnam. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Hudson, Patrick. (1995). Introduction. In Rutherford's Dreams: A New Zealand Science Fiction Collection, ed. Warwick Bennett & Patrick Hudson, 7-9. Wellington: IPL Books.

King, Michael. (2007). The Penguin History of New Zealand Illustrated. Auckland: Penguin.

Mann, Phillip. (1995). Lux in Tenebris. In Rutherford's Dreams: A New Zealand Science Fiction Collection, ed. Warwick Bennett & Patrick Hudson, 92-112. Wellington: IPL Books.

Morrissey, Michael. (1985). Jack Kerouac Sat Down beside the Wanganui River and Wept. In The New Fiction, ed. Michael Morrissey, 125-31. Auckland: Lindon Publishing.

Ross, Jack. (2006). The Isle of the Cross. In Myth of the 21st Century: An Anthology of New Fiction, ed. Tina Shaw & Jack Ross, 84-94. Auckland: Reed.

Sargeson, Frank. (1946). The Hole that Jack Dug. In That Summer and Other Stories, 179-86. London: John Lehmann.

Shaw, Tina, & Jack Ross. (2006). Introduction. In Myth of the 21st Century: An Anthology of New Fiction, 7-9. Auckland: Reed.

Abstract:

New Zealand, as a nation, has been in existence for less than two centuries – whether one dates its assumption of sovereignty to the 1835 Declaration of Independence by the Confederation of United Tribes, the 1840 Treaty of Waitangi between Maori and the British Crown, or its attainment of Dominion status in 1907. The question of a separate cultural identity for this post-colonial, multi-cultural country has therefore always been a complex one, and one which has had a strong influence on much of our artistic expression to date: particularly, perhaps because of its inherent tendency towards the self-analysis only really possible within language, literature.

The fact that our most famous locally born writer to date, Katherine Mansfield, specialised in the short story has certainly helped to establish that as a vital genre here. This paper accordingly takes four successive anthologies of local short fiction – Frank Sargeson’s Speaking for Ourselves (1945), Michael Morrissey’s The New Fiction (1985), Warwick Bennett & Patrick Hudson’s Rutherford's Dreams (1995), and Tina Shaw & Jack Ross’s Myth of the 21st Century (2006) – and attempts to characterise their respective, overlapping visions of New Zealand identity by conducting a close reading of a representative story from each of them.

The essay concludes with a call for a new anthology which might attempt to give expression to this series of gradual erosions of our initial cultural certainties into something more adequate to the realities of our place in the world, both geographically and culturally.

•

(20/6-4/7/16; 28/10/16-8/2/17)

If you wish to self-archive your article, please use the accepted manuscript version for posting on your own website. You may further deposit the accepted manuscript version in any repository, provided it is only made publicly available 12 months after official publication or later and provided acknowledgement is given to the original source of publication and a link is inserted to the published article on Springer's website. The link must be accompanied by the following text: "The final publication is available at link.springer.com”.

FDHS [Fudan Journal of the Humanities and Social Sciences]. ISSN 1674-0750. DOI 10.1007/s40647-017-0170-2 (Shanghai: Fudan University, 2017): 1-19.

[available at: http://rdcu.be/pqnG (21/2/17)].

[9086 wds]

•

No comments:

Post a Comment