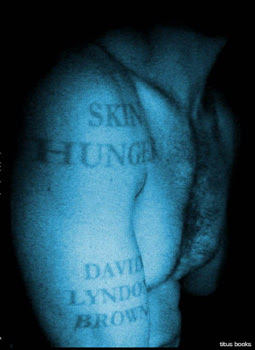

David Lyndon Brown. Skin Hunger. ISBN 978-1-877441-08-0. Auckland: Titus Books, 2009. RRP $NZ22.95.

Bernadette Hall. The Lustre Jug. ISBN 978-0-864736-08-6. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2009. RRP $NZ25.

Kevin Ireland. Table Talk: New Poems. ISBN 978-1-877340-24-6. Auckland: Cape Catley, 2009. RRP $NZ25.99.

Jessica Le Bas. Walking to Africa. ISBN 978-1-86940-446-8. Auckland: Auckland University Press, 2009. RRP $NZ24.99.

Frankie McMillan. Dressing for the Cannibals. ISBN 978-0-9864529-0-1. Christchurch: Sudden Valley Press, 2009. RRP $NZ25.

Brian Turner. Just This: Poems. ISBN 978-0-864735-91-1. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2009. RRP $NZ25.

Richard von Sturmer. On the Eve of Never Departing. ISBN 978-1-877441-09-7. Auckland: Titus Books, 2009. RRP $NZ29.95.

Jessica Le Bas’s new collection of poems about her daughter’s dreadful descent into depression and the labyrinthine processes of the Mental Health system, Walking to Africa, is similarly hard to diagnose. It’s an odd decision, to say the least, to make someone else’s suffering the subject of such a set of confessional poems.

What one is forced to admire about Le Bas, though, is her honesty about her own reactions. She portrays herself (by turns) as snooty to the various counsellors and diagnosticians in the hospital system, irritated by her daughter’s repeated relapses and refusals to get well, and quite simply not up to the challenge of making sense of it all. The conclusion to her book, where she suggests that poetry might provide some solace if not a cure for the whole conundrum, is almost Rupert Brooke-like in its crazed optimism (“A body of England’s / Breathing English Air …”):

There is poetry

Little mouthfuls of life

freeze flowing and condensed

a chocolate spoon full

One each day. [84]

But it’s honest. That’s what gets me about it. She’s not saintly, not all-knowing, wise, patient – she’s human, flawed, peevish. Maybe that’s worth saying at such length. And maybe not. Who knows? In any case, it’s one possible set of reactions to the sleep of reason. That’s how I read it, at any rate.

Another reaction to the sheer pain and meaninglessness of things, a more Romantic though certainly no less honest one, can be found in David Lyndon Brown’s intense, uncompromising début collection Skin Hunger. His own way of transcending the quotidian is through sex and friendship (and possibly a bit of substance abuse) and yet none of it ever seems quite enough:

[84-85]

and what of that incendiary LOVE

ABJECTION?

OBEISANCE?

ABSOLUTION?

And yet and still and yet and still

IT

IS

BEAUTIFUL

And then there are the strange stumbling noises, the throat-clearings and hesitations modulating into still semi-polished crooning (rather like a late Dennis Potter screenplay) of Kevin Ireland’s eighteenth (no less) collection of poems Table Talk. You’d think after last year’s How to Survive the Morning and the year before’s Airports and Other Wasted Days that there would be little to add to the chronicle of physical infirmity and gradual loss of friends which seems the inevitable accompaniment of his old age, but Ireland seems determined to keep on talking. As long as Cape Catley keeps on publishing them, one feels, there will be more books of this sort from Ireland. Why? Well, in “The Poem that wrote itself”, he explains:

This is the poem that I have been waiting to write.

I have no idea where it is going, there is just

this desire, which grips and shakes the bars of its words,

to break free, eat fire and sip salt spray on the wind. [72]

“I have no idea where it is going,” he admits, but concludes “I must acquire a new word-list / to live with you forever in flames and spindrift.”

It’s taken a long time for Kevin Ireland to get to this stage of raging against the dying of the light, this late Yeatsian refusal to be respectable and roll over. The sheer clumsiness of some of these poems constitutes their strength, for me. Like Brown and Le Bas, the subject he is measuring himself against is darkness and chaos. Of course he’s not up to the task, but then who could be? Keeping on going is in itself a kind of heroism, here.

There are good moments and bad moments in Brian Turner’s rather more curmudgeonly new collection Just This. Just this, eh? A lot of wandering around the high country, a lot of whinging about city-folk and their failure to understand same, a lot of the mixture-as-before, was ( I have to admit) my immediate reaction. Perhaps the worst example is the set of Helen-bashing verses “A PM in the High Country: “Here’s there’s no political mileage / in point-scoring, in tantrums … / Is it / too late for her to be de-bugged?” Self-parody, really.

But this is a collection that continues to surprise and test its reader the more it is scrutinized:

the whole family singing of taking high roads

or low roads to the very same place in the end,

Mum with tears in her eyes

for reasons I never

fully understood and never will. [109]

If you don’t get that then there’s no point in persevering, really. And I’m not talking about “fully understanding” Turner’s lines – rather about seeing what he’s getting at, that understatement is not so much a device as a necessity for a generation as soul-calloused as ours.

Richard von Sturmer is more officially concerned with soul-searching, one might say. He is, after all, a Zen Buddhist, with an impressive and original list of meditative poetic and prose-poetic books to his credit. On the Eve of Never Departing brings together the underlying surrealist with the sedulously cultivated monk. At times the non-violence of it all almost overwhelms one: the spiritual pilgrimage through the turbulent modernist of industrializing China, like a blind John Clare; the weird colloquies with monkeys in the Auckland Zoo, or eels off the wharf in Lake Pupuke ... I’m not sure if the collection ever becomes more than a collection, to be honest: it remains an assemblage of disparate pieces from disparate times. He is finally, it seems, not up to the challenge of his subject matter.

Given the nature of that subject matter, though – subsuming the turbulence of a deeply-wounded psyche under the unruffled surface of his own Buddha nature, providing instruction to an embattled world in how to do the same – failure is a foregone conclusion. He isn’t Christ, after all – or Prince Gautama for that matter. But he is an honest man and an honest writer, and – frustrating though it can be at times – his honesty and sheer goodness shine out in this as in his other books.

And Bernadette Hall? What of The Lustre Jug? Top o’ the morning to you, begorrah. Is it yourself that’s there? A certain recrudescence of stage Irishry seems to be an expected corollary of receipt of the Rathcoola Fellowship. As with Fiona Farrell’s Pop-Up Book of Invasions the year before last, Hall has obliged with a number of evocations of the Republic:

Michael Collins was killed in an ambush not far from here,

parts of Cork city were razed by the Black and Tans,

all of which gets me thinking that sometimes

I’m the daughter of a laughing Irishman,

sometimes of his assassin. [43]

The superficiality of it all is feigned, of course. The act, the “laughing Irishman”, is just one more way of dealing with the inassimilable – the appalling, unspeakable tragedy of Ireland’s bloody last century: forget about the famine, now it’s the treaty, the troubles, the civil war, the cultural ravages of the tiger economy. The Irish section of Hall’s book concludes tellingly with the poem “Guilt,” where she transposes the impossibility of dealing non-perfunctorily with such suffering – for other people – with the simple death of a fox:

Maybe she died of starvation.

Being a vegetarian, I could have left

a bowl of porridge out in the garden.

I did think about it but it seemed ridiculous. [47]

Now that really is admirable – and honest – writing: subtle, effective, and to the point.

So, last but not least, let’s come to Frankie McMillan’s’ first collection Dressing for the Cannibals. She understands “how the inherent associational fluency of words can be arranged to wonder about how it is that ‘we are so mysterious to ourselves and to the world’,” apparently, or so says Michael Harlow on the cover. Appearing thus under Harlow’s aegis does give some clues to her overall direction. Much of her prose poetry is clearly influenced by him – “the piano learns to swim” is, in fact, a kind of sequel to the older poet’s “This is the Piano’s Birthday.” What’s here that’s hers, then? I guess an empathy and understatement with suffering. In “I meant those kids no harm,” for instance, the witch from Hansel and Gretel concludes:

they wanted adventure, a hut in the words

a candle of their own to burn

See how you like it, I told them, see what it is

this wide cold world [57]

That’s nice, but still a little facile, perhaps. Not so the poem “Miss”:

In cities all over the world

missing girls

rise to pull on their cotton socks

and run for the no 6 bus

The whimsy here seems far from arbitrary – a mask, rather, for the unspeakable: the sleep of reason that comes with the fall of night:

Sometimes a miss

will join with a mister

and in evening picnics in the woods

they find each other pleasing [59]

There’s a lot to make sense of in this (or, for that matter, any other) world. Worlds of brutal fact, of cosmetic cleanliness and order; worlds of madness, or the imagination. Poetry can be a way of disciplining one’s primeval shrieks and grunts into something more ordered, if not – in the final analysis – necessarily more meaningful. Goya died, a deaf and misanthropic recluse, in a house which it turned out he’d covered almost entirely with strange dark frescoes.

Why did he bother? Well, why not? I’m glad he did. Those paintings (I feel) can somehow help when one feels most miserable. Somebody else understands. Someone is prepared to own up, to bear witness to the sufferings of war, of intolerance and ignorant cruelty: the Inquisition. I’m afraid that you can’t persuade me that it’s all five-finger exercises, pointless vanity, a waste of time.

I’m glad, too, that these seven poets bothered. I don’t care where they perch in artistic pecking order – I’m not interested in sorting them into some kind of honour roll of merit. I understand – I think I understand – what they’re facing up to, why they made some of the choices they did. I’ve learnt a lot by reading them, lessons for my own blind progress. Hopefully none of them will make anyone’s life any worse.

The biggest risk-taker there would have to be Jessica Le Bas. Does she really have the right to write so about her own daughter? I don’t know. That’s a question for the two of them to resolve, not me. I do believe in the purity of her motives, the honesty of her self-scrutiny – the fact that she believes that it might help others in similar trials. Telling them it’s okay not to be a saint. Who knows, it might even make some of us feel a bit better.

What more can one really hope of any poem?

No comments:

Post a Comment